Introduction to the Hematopoietic System

On this page...

Hematopoiesis

Hematopoiesis is the process of blood cell formation. It originates from hematopoietic stem cells located in the bone marrow of the femurs, pelvis, ribs, sternum, and other bones. These stem cells have the unique capacity to differentiate into all types of mature blood cells.

Hematopoietic stem cells proliferate, which is the process during which the cells in the bone marrow are instructed to produce new blood cells or stop producing new cells. For example, some of the daughter cells remain as unspecified, undefined, or uncommitted to a hematopoietic stem cell so that the pool of stem cells does not become depleted. This is a unique process to stem cells and is incredibly important to our survival.<.p>

An under or over production of a certain type of blood cell type or cell line will result in an unbalance of cells circulating through the body. This could cause disorders like anemia.

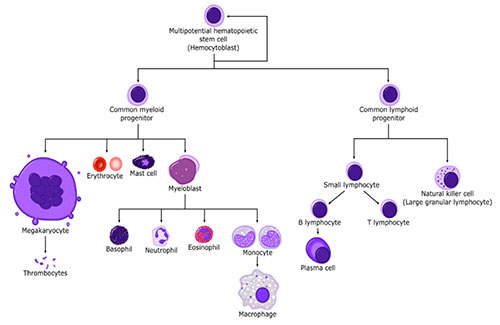

The other daughters of hematopoietic stem cells become myeloid and lymphoid progenitor cells. These cells create the big divide in stem cell hematopoiesis – myeloid and lymphoid. From these two lines come all of the blood cell lines.

Myeloid and Lymphoid progenitor cells can each commit to any of the alternative differentiation pathways that lead to the production of one or more specific types of blood cells.

Illustration of the multipotential hematopoietic stem cell (hemocytoblast) pathways.

Blood Cell Lineages

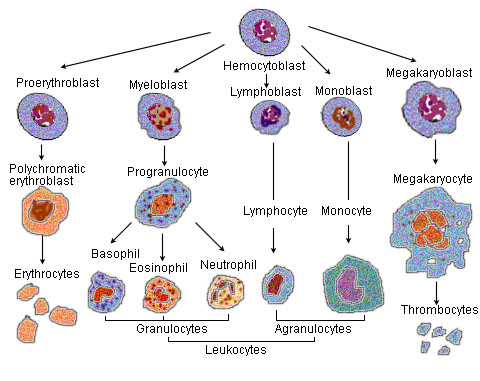

Cell line differentiation is the process by which a less specialized cell becomes a more specialized cell type. Early cellular differentiation occurs during embryonic development and continues into adulthood. Adult stem cells divide and create fully differentiated daughter cells during the routine processes of tissue repair and during normal cell turnover.

During the process of hematopoiesis, the blood system regulates the proliferation and differentiation of cells as they commit to and mature into different lineages or cell lines.

Illustration of the development of the formed elements of the blood.

At the end of the cell life cycle is the progress of programmed or intentional blood cell death. Hematopoietic and Lymphoid cells are not intended to live very long individual lives. The body sends signals to older cells that their work is done, and it is time to self-destruct. This is a biochemical process and is just as important to maintain balance as is the production of new cells. However, sometimes blood cells fail to recognize or respond to the biochemical signals that it is time for the cell to die (cell death or apoptosis). This can once again lead to an excess of a specific type of cell in the bloodstream.

Growth factors, genes, and proteins regulate the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic and lymphoid cells during hematopoiesis. These influences may either repress or activate hematopoiesis or apoptosis-in other words things get turned on and off-and may stay on or off if not regulated properly.

When the cell development cycle is interrupted or impaired, normal hematopoiesis ceases. If this cellular dysregulation continues, the likelihood of malignancy increases. This is a process called oncogenesis, which is the process by which normal cells are transformed into cancer cells. This is also called Carcinogenesis.

The same factors that affect proliferation and differentiation are looked at by the pathologist when conducting specific tests.

Some factors affecting proliferation and differentiation are in fact the proteins, genes, and growth factors that the pathologist is looking for when conducting specific tests.

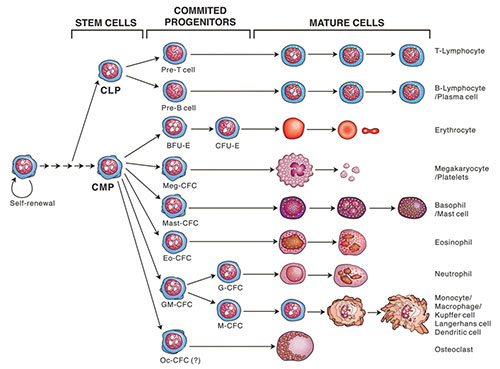

Boodlines. The eight major hematopoietic lineages generated by self-renewing multipotential stem cellsB.

Source: Donald Metcalf, AlphaMED Press, 2005, http://www.alphamedpress.org

The image above illustrates significant milestone events encountered during the process of hematopoiesis when the stem cells either commit to becoming mature cells (lymphoid or myeloid) or if they commit to regenerating stem cells.

Types of Blood Cell Lineages

All blood cells are divided into two main lineages: myeloid and lymphoid.

Myeloid cells are a type of red blood cell that are involved in such innate immunity, adaptive immunity, and blood clotting.

The myeloid lineages include

- Basophils (example of malignancy: Acute basophilic leukemia)

- Dendritic cells (example of malignancy: Dendritic cell sarcoma)

- Eosinophils (example of malignancy: Chronic eosinophilic leukemia)

- Erythrocytes (example of malignancy: Acute erythroid leukemia)

- Macrophages (example of malignancy: Erdheim Chester disease)

- Megakaryocytes (example of malignancy: Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia)

- Neutrophils (example of malignancy: Chronic neutrophilic leukemia)

- Platelets (example of malignancy: Polycythemia vera)

Lymphoid cells, which a type of white blood cell, are the cornerstone of the adaptive immune system. They are derived from common lymphoid progenitors.

The lymphoid lineages include

- B-cells (example of malignancy: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma)

- T-cells (example of malignancy: Peripheral T-cell lymphoma)

- NK-cells (example of malignancy: Aggressive-NK leukemia)

Both myeloid and lymphoid cell originate in the bone marrow. This results from a mature B or T-cell undergoing malignant transformation and disease progression, as well as proliferation and/or differentiation regulation abnormalities.

Plasma Cell Myeloma is an example of a B-cell neoplasm originating in bone marrow.

There are 21 different lineage tables in the 5th edition of the WHO Blue Book for Hematolymphoid Tumors. These 21 different groupings stem from either the Myeloid lineage or the Lymphoid lineage. A complete listing of specific histologies that are included in each lineage table can be found in the Hematopoietic Manual, Appendix B2.

| Table ID | Name | Myeloid/Lymphoid |

|---|---|---|

| B1 | Myeloid precursor lesions | Myeloid |

| B2 | Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) | Myeloid |

| B3 | Mastocytosis | Myeloid |

| B4 | Myelodysplastic syndromes | Myeloid |

| B5 | Myelodysplastic/Myeloproliferative (MDS/MPN) | Myeloid |

| B6 | Acute myeloid leukemia | Myeloid |

| B7 | Secondary myeloid neoplasms | Myeloid |

| B8 | Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms | Myeloid |

| B9 | Acute leukemias of mixed or ambiguous lineage | Myeloid |

| B10 | Plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms | Myeloid |

| B11 | Langerhans cell and other dendritic cell neoplasms | Myeloid |

| B12 | Histiocyte/macrophage neoplasms | Myeloid |

| B13 | Tumor-like lesion with B-cell predominance | Lymphoid |

| B14 | Precursor B-cell neoplasms | Lymphoid |

| B15 | Mature B-cell neoplasms | Lymphoid |

| B16 | Hodgkin lymphoma | Lymphoid |

| B17 | Plasma cell neoplasms and other diseases with paraproteins | Lymphoid |

| B18 | Tumor-like lesions with T-cell predominance | Lymphoid |

| B19 | Precursor T-cell neoplasms | Lymphoid |

| B20 | Mature T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms | Lymphoid |

| B21 | Mesenchymal dendritic cell neoplasms | Myeloid |

Having a general knowledge of the lineage tables can be a huge help to registrars as they are abstracting Hematopoietic neoplasms.

Updated: December 2, 2025